The Panama Canal was listed as one of the Seven Wonders of the Industrial World in a BBC miniseries produced in 2003. A marvel of engineering, the story behind it is truly incredible. Almost everyone has heard of it, but few know much about it.

We had the privilege of taking a cruise from Fort Lauderdale to Los Angeles in November which crossed from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the canal. The actual crossing takes eight hours.

The Atlantic side begins at the bottom of the scoop of Limon Bay where an inlet leads to the Gatun Locks. Everyone was crowded onto the decks to watch as we entered the locks.

The map below shows the Panama Canal. To call it a canal is a bit of a misnomer as it is actually a series of waterways that includes a bay, a set of locks, a man-made lake, a river, an actual canal, and another two sets of locks towards the Pacific side. Click on the plus or minis signs to zoom in or out on the map below.

The first European to cross the Isthmus of Panama was Vasco Nunez de Balboa who, accompanied by 1000 natives and 190 Spaniards, made the 40 mile crossing and sighted the Pacific Ocean in September 1513. He claimed the Great South Sea and all shores washed by it for King Ferdinand of Spain.

An overland route was established and the Spanish conquistadors who conquered vast territories of South America would ship gold from Peru to the town of Panama on the Pacific where it would be transported to the Atlantic by mule train.

From the mid-1500s to the mid-1700s, this route transported Spanish gold as well as silver from Mexico to be on-shipped twice a year to Spain.

The British eventually ousted the Spaniards from much of the Caribbean to claim dominance in the area. With the discovery of gold in California in the mid-1800s, the Americans now had an interest in the Panama crossing.

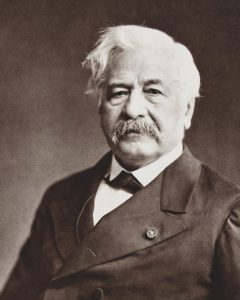

By 1875, the French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had built the Suez Canal a few years before, expressed an interest in building a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. The Suez Canal was 120 miles long. The Isthmuzs of Panama was only 40 miles across. What could go wrong?

In fact, de Lesseps success at Suez was part of his undoing. The Suez was a sea-level canal dug through sandy dessert. The Isthmus of Panama was a treacherous route that crossed vast jungles infested with yellow fever and malaria bearing mosquitoes.

De Lesseps was adamantly against building locks, believing a sea-level canal would do just dandy. French civil engineering was the best in the world at the time and the first crew of French engineers arrived in 1881.

Over twenty years of effort by the French ended in failure. Over 20,000 men died of yellow fever and malaria in the effort. 800,000 investors were wiped out. The de Lesseps were prosecuted in a huge bribery scandal. Even the late involvement of Gustave Eiffel could not save it. A new company took over in 1894, the same year Ferdinand de Lesseps died, and kept what was built in saleable condition. Eventually the American government took over in 1904 and finished the canal in 1914.

The Americans took a different approach to the French. They maintained and expanded the work done on the Culebra Cut which runs for nine miles from the Chagres River (Gamboa on the map) to where today’s Pedro Miguel Locks (not far east of the Milaflores Locks) are located. But they dammed up the river in 1906 at the Atlantic Ocean, creating the largest dam and the largest man-made lake in the world at the time. Most of the distance traveled through the Panama Canal goes over the Gatun Lake and a section of the Chagres River.

The original locks have two channels, one going in each direction. A parallel set has recently been built to accommodate larger ships. They were opened in 2016. We took the old set of locks, the original Panama canal.

The operation of the locks is impressive. The Gatun Locks raises ships 85 feet above sea level in three stages to reach Gatun Lake. Below is a video of the gates closing behind us at the first lock.

After the gates are closed, water is allowed into the lock to raise the ship to the next level. The water flow is quite swift and you can actually see it going up. The video below captures the water flowing. Watch the water level against the lock gate to see how quickly it rises.

Ships do not go through the Panama Canal’s locks on their own power. They are towed through the locks by train locomotives known as mules. Two mules on each side, fore and aft, tow the vessel.

As vessel traffic is in both directions, we entered the middle lock at the same time that a ship going in that opposite direction entered. The video below shows our ship and the cargo vessel Chasselas passing each other as we enter the middle locks.

About a thousand ships passed through the canal the first year it opened. In 2008, 14,702 ships passed through. It brings in revenue of $2 billion a year on costs of just $600 million. The Americans retained control of the canal until it was handed over to Panama in 1999. The treaty stipulates that the U.S. retains “the permanent right to defend the canal from any threat that might interfere with its continued neutral service to ships of all nations.” Panama has complete control over operations and has, in fact, expanded and improved the canal’s operations since taking control.

We were on a lower deck while passing the Charrelas and notices the shadows of people on the upper deck against the top of the freighter. An interesting sight.

Finally we were in the third of the Gatun Locks and ready to enter Gatun Lake for the sailing to the Pedro Miguel Lock some forty miles away.

Now I don’t know if this ritual is carried on by all cruise ships passing the canal, but our ship had an elaborate ritual, the Transitting the Panama Canal Official Ceremony, at noon on that day. The local native Chief Seneco and his wife, accompanied by two “mermaids” took seats of honor at the Centrum as the ship’s executive staff paid homage to the Chief and asked permission to travel across their territory.

Our Cruise Director, Steve Davis, conducted the ceremony which included executive staff members doing penance for alleged transgressions, like knocking on stateroom doors in the middle of the night as a prank, using too much hair gel, spiking drinks in the day spa, or turning up the sensitivity of the metal detectors so everyone would beep on returning from a shore excursion.

Punishments for these transgressions got moire severe as the rank of the executives staff members got higher. First they had raw eggs mashed on their heads, then they were pied, then spaghetti poured on with tomato sauce, and when the Hotel Director and another fellow were brought forward, they had to kiss a fish.

Cruise Director Davis revelled in this melee as he announced them and “punishments” were inflicted. But as the ceremony reached an end, Chief Seneco commented that there was one transgressor who had not been brought forward. Yes! Cruise Director Davis himself. Below is a video of Davis getting his come-uppance.

We continued on through the Gatun Lake until we got to the mouth of the Chagres River. The Chagres River used to flow all the way to the Atlantic but now most of it has become the Gatun Lake. What remains is navigable and dotted with little islands. Our excursion the next day took us by bus to where the Chagres meets the Culebra Cut and from there we took a motor boat along the Chagres to the islands near Gatun Lake. The islands are populated by monkeys.

We saw a number of freighters along the way including a liquid natural gas carrier.

The Culebra Cut is an actual canal, started by the French and completed by the Americans. It runs nine miles from its junction with the Chagres River to the Pedro Miguel Locks.

All in all, the transit of the Panama Canal was an entertaining and informative event. I bought a book about the canal on board and the history behind it is a fascinating story of daring and courage, hardship and failure, political intrigue, and ultimate triumph. Truly one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.

Additional Links of Interest